In the olden times when weeks were three days long and daytime TV was a still photo of a young girl losing noughts and crosses to a toy clown, my family bought me a bunch of premium bonds. If you don’t know, premium bonds are a kind of 1950s national lottery: you give an agency of the government some money, they give you some numbers, and those numbers take part in a monthly draw forever. You might win a prize each and every month; you might win nothing, ever. It’s all in the hands of the gods, in this case the god called ERNIE, the random number generator for premium bonds (in the 1950s all computers had to be given names so people wouldn’t grab pitchforks and torches and raze the building).

Fast forward a few decades and a couple of addresses and naturally NS&I, the priests who tend the dead pixels of ERNIE’s 2013 descendant, no longer know where I live. Having found my premium bond holder’s number and discovered I won £50 nine years ago that’s still waiting for me to claim, I thought I’d sign up to their online service at nsandi.com and ask for my winnings.

“Complete the online and phone registration form”, said the website. By which they mean, it turned out: give us all the pertinent details and we’ll generate a PDF for you that includes those details, which you must then print, sign, have witnessed, and then post.

Not the mightiest of faffs, and I suppose fair enough — though it’s hardly the most fraud-proof authenticator. Dutifully, and via PC World to address the inevitable empty printer cartridge, I did as I was told and posted the form.

A few days ago I received two letters, in identical envelopes, with identical plastic windows showing identical address formatting. Neither said NS&I on the outside, but they both evidently had the same sender.

One letter gave me my NS&I number: an eleven-digit identifier. My username.

The other letter contained, beneath a fancy-dancy pull-off plastic strip, an eight-character alphanumeric temporary password for my NS&I account.

So they sent separate letters for username and password for security, but in the same post so they’d likely arrive at the same time. Not particularly secure. Surely better, if they want to keep these things separate, to send them by different means: number by text message, password by post, or something. Anyway.

The password letter said I’d need to choose a new password for the site on first login. Helpfully, it gave the constraints:

The password you choose must have between 6 and 8 characters. You need to include at least one number, at least one special character, as well as a mixture of upper and lower case letters.

I understand the purpose of the character type constraints. Although enforcing a number and a special character reduces the total entropy of a password (an attacker knows that one of the characters has only ten possibilities — the digits 0-9) it increases the strength of the average password. It forces people who’d normally use “password” to use, say, “pAs5w.rd”. But I’d bet a large proportion of people stick the number and punctuation on the end, with an upper case letter at the start: “Foobar9!”. How much more secure is that than “foobar”? Not much. Users subvert constraints, because security trades off against usability.

To illustrate how likely this particular pattern is, the password letter includes this text just after the constraints:

An example is Uhsd895* (do not use this example for your own password).

In any case, a maximum length of eight characters for a password is, these days, laughable.

After ranting about this on Twitter, I left it a day or two. Yesterday I thought I’d try logging in.

Stand by your beds, I’m switching to present tense. It’s more dramatic.

On the first screen, the site asks for my surname and my NS&I number. OK.

On the second screen it wants two characters from my password (hopefully these are randomly chosen). Hmm. Presumably this is intended to defeat keyloggers (in fact it’s not usually much help), but unfortunately it also defeats password managers that like to fill in password boxes for you. And it might also mean NS&I is storing passwords in its database in plaintext.

Next screen: choose a new password. Here it doesn’t tell me what the password constraints are. I presume they’re the same as in the letter. I generate a random password in my password manager, limiting it to eight characters, and this is accepted.

Next screen: security questions. Five of them. All mandatory. Each with a separate picklist of choices. At least one of the available questions seems US-biased (wanting my “first-grade teacher”). Others are ambiguous (“favourite sports team”) or easily discoverable (“university”) or can be socially engineered.

Right, done that, is that everything? No.

Below that, three boxes for security phone numbers. Thankfully only one is mandatory.

Am I done now? Not yet.

Next screen: I must select one from about eight or ten thumbnail images. My selection will be displayed on the login page as “reassurance” that I’m on the site I think I am.

Am I done now? Nope.

Below that: I must enter a “login phrase” as yet further “reassurance” when I log in. I enter something short and pithy.

And then, finally, I’m done. I have hauled my weary body through the maze of twisty passages all of limited utility, and have made it to NS&I’s secure website where I can claim my £50.

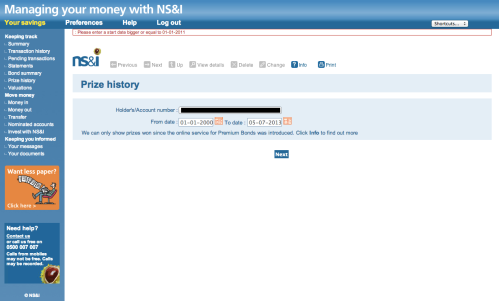

I click “Prize History” on the sidebar of the early-noughties design. I select my premium bond holder number from the list of two items (“please select” and my number). To select a date range there are two date pickers dug up from about the late eighteenth century which open actual new browser windows with ugly calendars. I decide to look between January 2000 and now, because, well, why not. (I don’t bother to read the text below, which nobody ever reads, and which says “We can only show prizes won since the online service for Premium Bonds was introduced. Click Info to find out more.”)

I click Next. There, in the world’s tiniest writing, several miles from the most appropriate place: “Please enter a start date bigger or equal to 01-01-2011”. (The Info popup says much the same thing, but in English.)

Hang on. I won my prize in 2004. Are you telling me the unclaimed-prize checker you don’t need an NS&I account to use has more data, going back further in time, than the hoop-tumbling monstrosity that is the secure, authenticated account-holder site?

It’s at this point I realise I’ll be writing this blog post.

OK, I’ll play their game. I change the start date to 01-01-2011 and click Next. It whispers another error message: “ZTS90009 : Please enter a start date bigger or equal to 08-07-2011”. No reason given.

This sort of half-baked rubbish no longer surprises me, so I change the picker to exactly that date. Here’s what it squeaks now, in that same tiny font, just as if it were an error: “ZTS90007 : There are no prizes to display.”

Thanks for that.

How do I claim my £50? After much clicking around I find nothing on the authenticated site that lets me do that.

I log out, huff and puff, and hunt down the website’s feedback form. I keep my comments and my question short: essentially, “I’ve got an NS&I account. How do I claim an unclaimed premium bond prize?”

An hour or so later, I receive a reply by email:

To claim your outstanding prize please can you write to us quoting :

1. Your name and address

2. Your holder’s number

3. The prize details as stated on the website

To make sure that we provide the highest levels of security, we require the signature of the holder to enable us to issue any replacement warrants.

You know, something tells me they haven’t upgraded ERNIE since about 1964, and it’s still running their IT. And I suspect I might shortly be booking a very pleasant railway journey to NS&I Glasgow, armed with a pitchfork and a flaming torch.